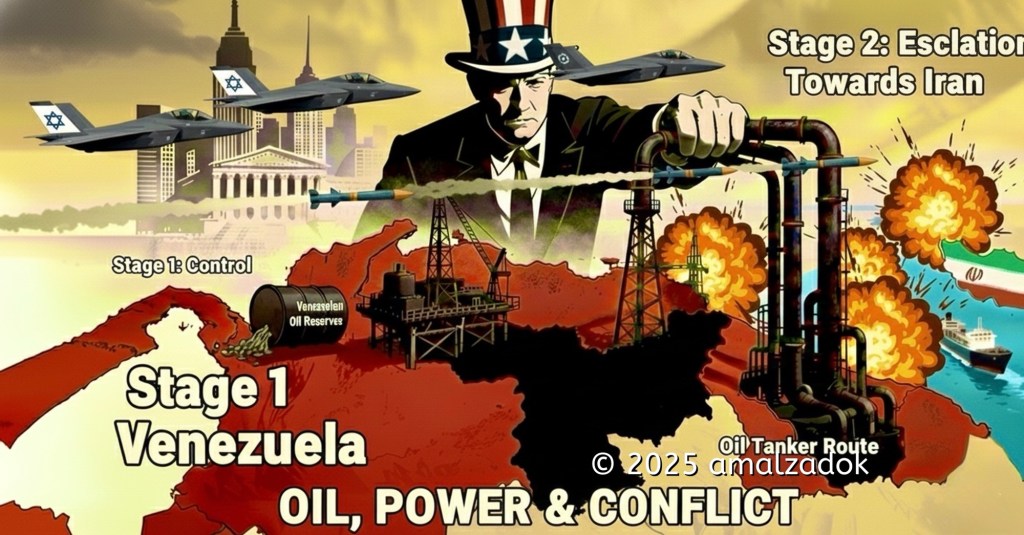

The pattern of U.S. moves on Venezuelan oil, combined with the strategic vulnerability of the Strait of Hormuz, makes it plausible that Washington is positioning itself for a future confrontation with Iran in which Gulf oil flows could be disrupted, while Venezuelan crude serves as a non‑Hormuz fallback for the U.S. and Israel. The recent U.S. attack on Venezuela, the capture of President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, and their transfer to New York on narcotics and related charges do not undermine this thesis; they expose how “drug enforcement” has become the legal façade for a resource‑seizure operation aimed at securing oil for a long war scenario.

The scale of Venezuela’s oil treasure

Any geopolitical argument about Venezuelan oil must start with sheer scale. Venezuela today holds the largest proven oil reserves on the planet, with estimates around 300–303 billion barrels, or roughly 17–18 percent of all known reserves, surpassing even Saudi Arabia. In other words, this one Latin American country, within flight distance of Florida, controls more oil underground than the entire United States, which has around 55 billion barrels of proven reserves.

Those reserves are not just large but strategically tempting. Much of Venezuelan crude is heavy, but U.S. Gulf Coast refineries are precisely configured to process heavy and extra‑heavy oil, historically imported from Venezuela and Mexico. In a world where Middle East supplies become uncertain, a political arrangement that gives Washington decisive leverage over the biggest single reserve base in the world is an energy security dream.

From sanctions to open seizure: Maduro in New York

For years, Washington relied on sanctions, asset freezes, and indictments to squeeze Caracas while stopping short of open war. The narco‑terrorism case filed in New York against Maduro and other Venezuelan officials framed the country’s leadership as a criminal cartel, preparing public opinion for more extreme measures. That legal architecture has now been matched by force: U.S. strikes on Venezuela, the capture of Maduro and his wife, and their transfer to New York on drug and criminal charges mark a historic escalation from economic warfare to direct regime decapitation.

Crucially, this escalation has been accompanied by unprecedented candor from Donald Trump about what comes next. He has publicly stated that the United States will “run” Venezuela “for now,” asserted that the U.S. “built” Venezuela’s oil industry in the past, and pledged that American companies will return to “rebuild” and tap its oil reserves—framing this as an open‑ended, effectively indefinite arrangement. In other words, the kidnapping of a sitting president on drug charges is not the consummation of a moral crusade against narcotics; it is the opening move in a new phase where Washington claims the right to administer, and profit from, the world’s largest oil reserves.

Why the Strait of Hormuz terrifies planners

The Strait of Hormuz is a narrow maritime corridor between Iran and Oman, the only sea exit for the oil‑rich Persian Gulf. In a typical recent year, roughly 20–21 million barrels of oil per day have transited this passage, about 20–21 percent of total global petroleum liquids consumption and over one‑quarter of all seaborne oil trade.

For decades, U.S. planners have quietly admitted what they seldom say openly: Hormuz is the soft underbelly of the global oil system. Around 80 percent of the crude that moves through it goes to Asian markets like China, India, Japan, and South Korea, but any serious disruption sends benchmark prices soaring and hits Western economies as well. Iran has repeatedly threatened to close or disrupt Hormuz if attacked and has demonstrated its capacity to harass or seize tankers, mine shipping lanes, and launch missiles at regional infrastructure.

In a full‑scale U.S.–Iran or Israel–Iran war, Hormuz does not need to be “completely shut” to cause chaos. Sporadic attacks, insurance spikes, and partial interruptions could remove several million barrels a day from the market for months, triggering price shocks, recession risks, and political backlash in oil‑importing democracies. This is the nightmare scenario for Washington: a conflict it believes is necessary for regional dominance colliding with its own population’s intolerance for sky‑high oil prices and economic free‑fall.

Linking the dots: Venezuelan oil as war insurance

Once the strategic importance of Hormuz is understood, U.S. behavior toward Venezuela stops looking random. Over the last decade, Washington has oscillated between punishing Caracas with sanctions and selectively easing restrictions to allow specific companies to re‑enter the Venezuelan oil sector under tight U.S. licensing. That pattern looked less like moral outrage and more like controlled positioning: weaken the Maduro government politically, while keeping the door open for U.S. and allied corporate access to the oil fields and infrastructure.

The post‑capture phase clarifies that logic. With Maduro removed and Trump openly declaring that the United States is taking indefinite control of Venezuela, Washington has maximal leverage to shape any “transitional” administration, dictate terms to state oil company PDVSA, and secure contracts for U.S. and European majors under the umbrella of American military and legal control. The same legal system that now holds Maduro and his wife on drug charges in New York will be used to claim the moral high ground, while U.S. energy companies are presented as the responsible adults arriving to restore order and “get the oil flowing again.”

To see why this matters for a future Iran war, imagine a scenario in which Iranian mines and missiles reduce tanker traffic through Hormuz by a third for several months. The resulting loss of millions of barrels per day would send global prices spiralling and force consuming states to scramble for alternative supplies. In that context, U.S.‑linked production in Venezuela—now explicitly under a U.S. “run” arrangement with indefinite control—could be ramped up and redirected to cushion the blow for North America and its closest allies. Washington would not be able to replace every lost Gulf barrel, but it would possess a strategic tap that others, especially rival powers, do not control.

Beyond democracy talk: energy security and Israel

Officially, U.S. leaders justify both the earlier sanctions and the latest military operation as a defense of democracy, human rights, and the integrity of the international drug control regime. Yet Washington maintains close partnerships with Gulf monarchies whose political systems are far more autocratic than Caracas at its worst, and Trump himself has pardoned or commuted sentences for U.S.‑linked traffickers and allies, undermining the supposed moral consistency of the “war on drugs.”

Set alongside the explicit promise that the U.S. will now “run” Venezuela indefinitely and unleash its oil potential, the common denominator is not liberal values but strategic oil supply and alignment with U.S. and Israeli military objectives in the Middle East.

Israel’s position is central here. Any large regional war involving Iran will almost certainly involve Israeli strikes on Iranian nuclear, missile, or command sites, prompting Iranian retaliation via proxies and potentially via direct attacks on Gulf infrastructure and shipping. Israeli and U.S. analysts openly discuss the risk of Hezbollah rockets, Iraqi militias, and Yemeni missiles converging on U.S. bases, desalination plants, and oil installations in a multi‑front escalation. For Washington, guaranteeing Israel’s ability to wage such a campaign without collapsing Western economies requires pre‑securing alternative oil streams that bypass the vulnerable chokepoints Iran can threaten. Venezuelan crude, moved across the Caribbean and Atlantic to U.S. and European refineries, would be largely immune to Hormuz and Red Sea disruptions.

Seen from this angle, the armed seizure of Venezuela’s head of state on narco‑charges, and Trump’s boast that the U.S. is taking indefinite control of the country, is not just a shocking violation of sovereignty; it is a step in a broader war‑planning architecture. Control over the world’s largest oil reserves in the Western Hemisphere acts as a form of insurance policy: if Iran makes good on its threats, the U.S. can lean on Venezuelan barrels to stabilize its own market and cushion the shock for its allies.

The logic of pre‑emptive control

Energy planners think in decades, not news cycles. The fact that most Hormuz flows currently go to Asia does not reduce the strategic risk for the United States; it amplifies it, because China and India could leverage their access—or their sudden loss of access—to reshape global power balances during a crisis. If the U.S. is preparing for a world where confrontation with Iran, and by extension with Iran’s partners, becomes more likely, then securing a hemispheric oil fortress in Venezuela becomes rational from a cold strategic standpoint.

By tightening sanctions, escalating to military strikes, physically removing the elected president under a cloud of drug charges, and now declaring indefinite U.S. control of the country, Washington builds a future in which any government in Caracas—friend, foe, or “transitional”—must negotiate oil policy under the shadow of American legal, military, and financial power. The goal is not merely to deny revenue to a hostile regime but to ensure that, when the next major war in the Middle East breaks out, those 300‑plus billion barrels sit within a system of contracts, infrastructure, and shipping lanes Washington can rapidly mobilize. In that scenario, Venezuela ceases to be a sovereign energy actor and becomes, in effect, a strategic fuel depot for a distant conflict in the Persian Gulf.

References

1.Al Jazeera. (2025, September 4). Venezuela has the world’s most oil: Why doesn’t it earn more from exports?

2.BBC News. (2026, January 3). What we know about Maduro’s capture and US plan to “run” Venezuela.

3.CBS News. (2026, January 3). U.S. strikes Venezuela and captures Maduro; Trump says U.S. will run the country.

4.CNN. (2025, June 23). What is the Strait of Hormuz and why is it so significant?

5.CNN. (2026, January 4). Maduro in U.S. custody after surprise Venezuela operation.

6.Fox Business. (2026, January 2). Trump pledges U.S. return to Venezuela oil industry after Maduro capture.

7.Fox News. (2026, January 3). Nicolás Maduro arrives in New York after capture; faces U.S. drug charges.

8.NPR. (2026, January 3). What are the charges against Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro?

9.NPR. (2026, January 3). Maduro faces drug charges in U.S. even as Trump freed other traffickers.

10.U.S. Department of Justice. (2025, February 4). Nicolás Maduro Moros and 14 current and former Venezuelan officials charged with narco‑terrorism, corruption, drug trafficking and other criminal charges.

11.ABC News (Australia). (2026, January 3). Donald Trump says US will run Venezuela for now after capture of Nicolás Maduro.

12.Los Angeles Times. (2026, January 3). Trump says U.S. will “run” Venezuela after capturing Maduro in audacious attack.

13.PBS NewsHour. (2026, January 3). A timeline of U.S. military escalation against Venezuela leading to Maduro’s capture.

14.The New Yorker. (2026, January 3). The brazen illegality of Trump’s Venezuela operation.

15.U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2023, November 20). The Strait of Hormuz is the world’s most important oil transit chokepoint.

16.U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2025, June 15). Amid regional conflict, the Strait of Hormuz remains critical oil chokepoint.

17.Worldometers. (2024, October 31). Venezuela oil reserves, production and consumption.

18.World Population Review. (2025, December 17). Oil reserves by country 2025.

19.Newsweek. (2026, January 3). Map shows how Venezuela’s oil reserves compare to the rest of the world.

20.Institute for Energy Research / IEA. (2024). Strait of Hormuz factsheet.

©️2026 Amal Zadok. All rights reserved.

Subscribe and never miss an article!

Leave a comment